Wolf VS Dog: The Forgotten History of Your Best Friend’s Domestication & Evolution

Dr. Libby Guise

“Ever consider what our dogs must think of us?,“

asks Anne Tyler

I mean, here we come back from a grocery store with the most amazing haul chicken, pork, half a cow. They must think we’re the greatest hunters on earth.”

Today’s pups are a far cry from their wolf ancestors. Our furbabies depend on us for their sustenance and care, and they provide us with satisfying companionship. How did the transition from predator-prey to master and four-footed-friend happen?

In this article, we’ll examine the theories about:

- When Were Dogs Domesticated?

- Where Were Dogs Domesticated?

- When and How Did Wolves Become Dogs?

- Evolution of Dog Breeds and Their Places of Origin

- Sporting dogs

- Hounds

- Terriers

- Working dogs

- Herding dogs

- Toy Dogs

- Non-sporting dogs

- Evolution of the Dog-Human Bond

- How Did Dogs Become Pets?

- Military, Working, and War Dogs

After we look at how we got from wolves to man’s best friend, we’ll learn about some special pups who faithfully served in the military.

Researchers studying the history of dogs rely on DNA and genome sequencing to map their transition from wolves to canine companions. While scientists generally agree that dogs evolved from gray wolves somewhere between 15 and 40,000 years ago, they have varying theories about the timing and location of their earliest domestication.

Some say that genetic evidence points to domestication starting in East Asia 15,000 years ago. But doglike fossils have been found in Europe and Siberia that date back more than 30,000 years. (1)

Early Dogs in Europe

Goyet Cave, Belgium - 31,700 years ago

Archaeological and fossil evidence of the origin of dogs may date back to the paleolithic period when humans were hunter-gatherers. According to Mietje Germonpré, a paleontologist at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, a 31,700-year old skull found in Goyet Cave, Belgium resembles that of Paleolithic Dogs. Germonpré reported,

“the Paleolithic dogs had wider and shorter snouts and relatively wider braincases than fossil and recent wolves.”(2)

Analysis of the remains shows these early dogs had a diet that included large animals like reindeer, horses, and musk ox. Germonpré and others suggest that the animals got handouts from the humans and may have helped the Aurignacian people with tracking and hunting.

Chauvet Cave, France - 26,000 years ago

In addition to the fossil record, there is archaeological evidence that humans and dogs co-existed many thousand years ago. There are side-by-side footprints of a child and dog in Chauvet Cave, France. The front paw prints show a shortened middle toe, which is characteristic of dogs. Charcoal from torch wipes on the walls places the time of this youngster’s visit at about 26,000 years ago. (3)

Analysis of the footprints revealed that the youth had a walking versus a running gait. The timing of the dog-like prints matches those of the youngster. For this reason, researchers believe the pooch may have been accompanying the child rather than chasing him.

Bonn-Oberkassel, Germany - 14,000 years ago

Scientists are not certain whether the footprints or fossil evidence above pinpoint the earliest domestication of dogs or mere co-existence. However, a more recent archaeological site in Germany has confirmed evidence of domestication. (4)

A burial site called Bonn-Oberkassel includes joint internments of humans and dogs dated to about 14,000 years ago. One of the pups included at this location shows signs of having contracted the canine distemper disease and of receiving care from humans to prolong its life.

Early Dogs in Asia

Razboinichya Cave, Siberia - 33,000 years ago

Skeletal remains found in a cave in the Altai Mountains of Siberia show a dog-like animal that suggests domestication. The bones are from about 33,000 years ago and may support the theory of multiregional taming of canines. Scientists suggest that the Last Glacial Maxim could have interrupted the domestication process in this case. These fossils help provide insight into the transitional stages between wolves and our modern furbabies. (5)

Yangtze River, South China - 5,400 to 16,300 years ago

A mitochondrial DNA study using data from dogs and wolves in China and across the Old World may demonstrate that modern canines trace back about 5,400 to 16,300 years ago to an area near the Yangtze River. In this research, scientists compared gene sequences for over 2000 dogs and nearly 50 wolves. They found that old world canines share a common gene pool and that the phylogenetic tree points to an area south of the Yangtze River as the point of origin. (6)

Multi-focal domestication

Evidence of early dogs and their domestication appears in several geographical locations. Canines also appear in art and literature of ancient cultures like Egypt, China, Greece, and Rome. While the first dogs seem to trace back to South China, other archaeological findings may support a multi-location theory for the transition of our four-footed companions from wild animals to man’s best friend.

Dog Domestication in the Ancient World

Dogs in America

Genetic evidence suggests that early American dogs most likely migrated from Asia prior to the flooding of the Bering Strait. The earliest fossil evidence of our canine pals, from about 10,190 to 9,630 years ago, comes from dog burial sites in the Lower Illinois River Valley. These internments, which demonstrate a human-animal bond, are the earliest known intentional graves of pups in the Americas. Other archaeological findings of early American dogs have been found in Idaho, Texas, Alabama, Missouri, and the Yukon Territory. (7,8)

In addition to fossil evidence of domesticated dogs, canines appear in the mythology of Mesoamerica.

- Mayans : Mayans bred furbabies for a variety of purposes including food, companionship, hunting, and protection. They believed these pooches accompanied the souls of the dead into the afterlife because of their swimming ability. Excavations in their area revealed co-burial of humans and dogs and temple wall inscriptions of pups.

- Tarascans and Aztecs : Tarascans and Aztecs raised dogs for the same purposes as the Mayans. Aztec mythology includes a tale about how their creator god, Texcatlipoca, made dogs from an earlier race of humans. This belief led the people to treat furbabies with great respect.

Dogs in Europe

Many ancient European cultures show literary and archaeological evidence of domesticated dogs.

- Ancient Greece : As with Mesoamerican cultures, dogs are a part of Ancient Greek Mythology. The three-headed canine Cerebrus was the guard-dog at the gate of Hades, and the goddesses Artemis and Hecate had four-footed pals. References to furbabies also appear in Plato’s Republic, writings of Socrates, and Homer’s Odyssey. Dogs were an important part of life in Ancient Greece. They served their masters as hunters, protectors, and companions. It was the Greeks who invented the spiked collar in order to protect their faithful friends from wolves.

- Ancient Rome : The Ancient Romans also saw pups as a favored pet. They relied on them for hunting, companionship, and protection. As a matter of fact, one ancient mosaic declares “Beware of Dog” (Cave Canem). In literature, Virgil and Varro both referred to canine guard dogs. The people also believed that their furbabies could sense disembodied spirits and sound the alarm before the ghosts did any harm.

- Norse Dogs : Norse mythology includes dogs in reference to the afterlife and healing. Like Cerebrus, the Norse dog, Garm, guarded the gates of Hel. In addition, Odin’s companion, Frigg, sometimes rode in a chariot pulled by pooches. Norse warriors frequently had their furbabies buried with them to protect and guide them in the afterlife.

- Celtic Dogs : Celts believed dogs had a magical ability to heal when they licked human’s wounds. These companion animals also appeared in their mythology. For example, their goddess of prosperity and healing, Nehalennia, often appears with a dog. In addition, a jealous fairy turned the goddess Turrean into an Irish Wolfhound. In early Irish culture, the people used pups for hunting, as food, for protection, and possibly as war dogs. Legendary tales from The Ulster Cycle, Táin Bó Flidais, and The Fenian Cycle include warrior canines.

Dogs in Egypt

As with other cultures, Ancient Egyptians included dogs in their mythology. They believed the jackal-dog, Anubis, guided departed souls to their final judgment in the Hall of Truth.

The canine had a place of an honored servant in Egyptian homes. Owners included their pal’s names on their collars. They held burial ceremonies for them to help provide a smooth transition to the afterlife. Families that could afford it, would have their beloved companions mummified like any other member of their clan.

Dogs in China

The domestication of dogs in China dates back about 14,000 years. The canines served as companions, guardians, food sources, and sacrificial animals. During the Shang Dynasty, people would sacrifice pups when they finished building palaces, tombs, or royal buildings. At one time, the Chinese killed and buried dogs in front of their homes or the city gates to guard against bad luck. People also used canine blood when taking an oath or making a pact.

The transition from wolves to dogs occurred about 20-40000 years ago as wild canines began to associate more closely with hunter-gatherers. To help pinpoint the timing of dog evolution, scientists use the development of new facial muscles, shifts in skull anatomy, behavioral changes, and genomic signatures.

Facial Muscle Anatomy

Among domestic animals, dogs seem to have a unique ability to communicate with their faces. From tilted eyebrows and “puppy-dog” eyes to the characteristic head tilt, our furry friends have a way of melting our hearts. Wolves, however, do not demonstrate the same level of ability to show such endearing expressions.

To understand why this is the case scientists studied differences in the facial muscles between wolves and dogs. There was little variation except for one muscle. Researchers found that most domestic canines have a muscle known as the levator anguli oculi medialis, which is essential for intense eyebrow movement. In wolves, the muscle is either less developed or replaced by connective tissue. (12)

Siberian Huskies, like the wolves, lack a developed muscle. This dog breed is more closely related to the ancient pups that first came from wolves.

These findings suggest that as dogs evolved from wolves, they developed an ability to communicate with humans. A new muscle around the eye allowed for raised eyebrows and widening of the eyes that mimics human emotion may have helped to develop the human-animal bond.

Skull Anatomy

It’s not just the soft tissue that’s different between dogs and wolves. The skulls of paleolithic canines, such as the one from Goyet Cave, Belgium show that these early pups had noses that were wider and shorter than gray wolves. The overall cranium was also wider than adult wolves. However, the skull anatomy resembles that of a juvenile wolf.

Madeleine Geiger conducted a study of the developmental stages of wolf and dog skulls to better understand the domestication of our domestic furbabies. She noted that the growth patterns between the two groups have only a few variations. One notable difference is that modern dogs appear to have slower skull development in comparison to wolves. Geiger argues that the delayed growth rate can lead to more altricial(helpless) young that would be easier to tame.

Because dog skulls maintain a juvenile appearance into adulthood, they have a more appealing look to humans. After all, who can resist a puppy face? We’ll talk more about this in a future section.

Behavioral Changes

The first behavioral step to domestication in the evolutionary process from wolf to dog was a loss of fearfulness of man. Some wolves learned to live close to humans in a mutualistic relationship. Over time, these animals became less prone to flee and more likely to trust people.

Modern dogs are more docile and show significant behavioral differences from their wolf ancestors.

- Dogs tend to be more affectionate than wolves. This contributes to building a dog-human bond.

- Dogs have fewer predatory tendencies than wolves. Domestication would be more difficult if canines wanted to eat their masters or other animals in the village.

- Dog genetic adaptations allow them to have a starch-rich diet. This allowed dogs to eat foods that humans were growing as well as hunting.

- Dogs reach sexual maturity earlier than wolves and have greater fertility.

- Dogs mark territory and sound alarm barks more frequently than wolves. As humans and dogs settled in one place, these behaviors made canines useful guard animals.

- Dogs accept strangers more readily than wolves. This allowed dogs to accept humans and other animals in the village.

- Dogs bond easily with humans while wolves bond best with other wolves.

Genomic Signatures

Before we turn to the genetic evidence of domestication, a few definitions are in order. Simply put, a genotype is a genetic makeup or DNA blueprint for an organism. A genomic signature is the portion of the DNA sequence that distinguishes one organism from another.

Scientists have researched fossil remains of ancient dogs and wolves and compared them with modern breeds to determine when and where canines diverged from their ancestors. In one study, Guo-Dong Wang and his colleagues compared whole-genome sequences of 12 gray wolves, 27 primitive Asian dogs, and 19 distinct modern breeds. The greatest level of genome diversity traced back to southern China around 33,000 years ago.

Jun-Fen Pang et. al. conducted a more extensive study comparing mitochondrial DNA of 1,543 Old World dogs, 33 dogs from Arctic America, and 40 Eurasian wolves. Their results suggest that modern dogs originated in Southern East Asia about 11,500-16,300 years ago and that they came from a common gene pool of about 51 female wolves. (13)

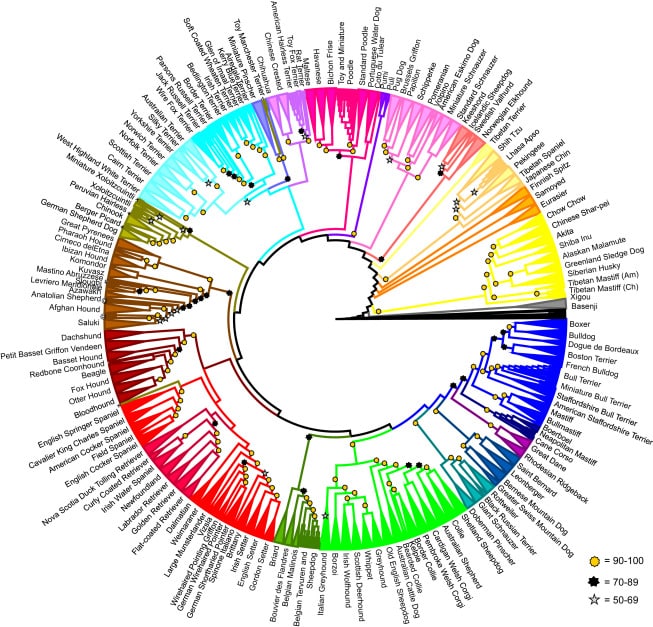

Once wolves evolved into ancient dogs and became domesticated, man started selectively mating them. Environmental influences like climate, food availability, and terrain also influenced which dogs would survive and reproduce. Over time, different breeds began to emerge.

Early humans bred pooches into 23 types, or “clades” such as herding, guarding or hunting dogs. Further differentiation occurred in the Victorian Era as people used selective breeding to emphasize specific physical traits abilities.

The American Kennel Club(AKC) defines a pure dog breed as one that always “breeds true”. In other words, if you mate two Labrador Retrievers, you’ll get Labrador Retriever puppies. Of 340 dog breeds in the world, the AKC officially recognizes 193 in their registry. For confirmation shows and other purposes, they group the different dog types into seven categories.

In April 2017, scientists published results of a DNA analysis of 1,346 dogs from 161 different breeds. Based on gene sequences, the researchers produced an evolutionary tree of dogs. By evaluating genetic variation and migration patterns, the data helps pinpoint where the different breed groups originated. (14)

Pups in the sporting group include Pointers, Retrievers, Setters, and Spaniels. Men selected these animals for superior bird hunting traits. Based on recent DNA analysis, researchers group the sporting dogs together on the phylogenetic tree and trace their origins to Victorian England.

Early people also bred canines to hunt warm-blooded quarry like rabbits and raccoons. The Hound group includes swift sighthounds like the Greyhound and sturdy scenthounds like the Dachshund and Bloodhound. These pups are known for their strong prey drives. The hounds are closely associated with the sporting dogs on the phylogenetic tree and likely originated in Europe.

Dogs in the terrier group include the Bull Terrier, Scottish Terrier, and West Highland White Terrier. These canines have shorter legs and feisty temperaments. Humans originally bred the longer-legged pups to dig up rodents. The bull terriers arose when people bred fighting breeds with terriers. This group of dogs originated in the British Isles.

Working dogs include the oldest dog breeds, such as the Siberian Husky. Humans bred these animals to help them with tasks like pulling sleds and guarding the home. They’re known for strength and intelligence. Other familiar breeds in this class include the Boxer, the Great Dane, and the Rottweiler. These pups trace back to some of the earliest dogs coming out of Siberia.

The herding dogs are also an older class of dog breeds. They were important in early cultures to help move and protect livestock. These pooches are intelligent, responsive, and full of energy. Because they work closely with their human counterparts, they needed to be readily trainable. Familiar members of the herding group include the Border Collie, German Shepherd, and Pembroke Welsh Corgi.

The phylogenetic tree doesn’t converge on one common ancestor for all the herding dogs. This is one reason that scientists believe that different breeds emerged independently in various geographical areas like the United Kingdom, Northern Europe, and Southern Europe. They postulate that different cultures bred dogs to manage the livestock that they managed.

The toy breeds are dogs of small stature. They tend to be affectionate and attentive and are popular as pets in dense population areas like cities. Some well-known breeds include Pugs, Chihuahuas, and Shih Tzus. Although these pups come from all around the world, they share a genetic mutation. Researchers discovered that all toy breeds have a common gene-regulating sequence that suppresses the release of growth hormone. This mutation traces back to the grey wolf.

The non-sporting group is the catch-all for breeds that don’t seem to fit in one of the other categories. This is a diverse collection of pups that includes the Bulldog, Dalmatian, and Poodle. Much like the toy breeds, this class has representatives from across the globe. Therefore, the common ancestor is likely the grey wolf.

We know that dogs are most closely related to the grey wolf and that dogs were the first animal that humans domesticated. Our canine companions have a uniquely close relationship with their masters. But how did the dog-human bond evolve? What events resulted in the transition from a wild predator to man’s best friend?

The change from a predator-prey relationship to a special bond required several steps along the way. As humans switched from a nomadic lifestyle to permanent dwellings, some wolves started to share territorial space with prehistoric communities. Over time wolves began to evolve into dogs, and a mutually beneficial relationship developed between canines and men.

Phase One: Social Tolerance

As people transitioned from hunter-gatherers to farmers, they began to establish more permanent settlements. Fossil remains show that in the early Pleistocene age, humans and wolves had overlapping habitats. During this time, the two groups started to live near one another and become accustomed to the other’s presence. This built a social tolerance in which two species exist in close proximity to one another without showing aggression, and it was a key first step to domestication.

One theory of why wolves started hanging around human villages is that they were “dumpster diving” or consuming the people’s refuse, such as organs of slaughtered animals. There are gaps to this hypothesis as early cultures tended to use every part of the animals they killed. It may be more likely that humans and wolves learned to work together to hunt larger prey in a mutually beneficial partnership. (15,16)

Phase Two: Social Attentiveness

As dogs and people grew more accustomed to one another, they developed a mutualism. During this time, pups learned to watch human actions closely and adjust their own behavior to facilitate cooperation. This is called social attentiveness. The ability to respond to their human counterparts helped early dogs take another step toward building a close bond.

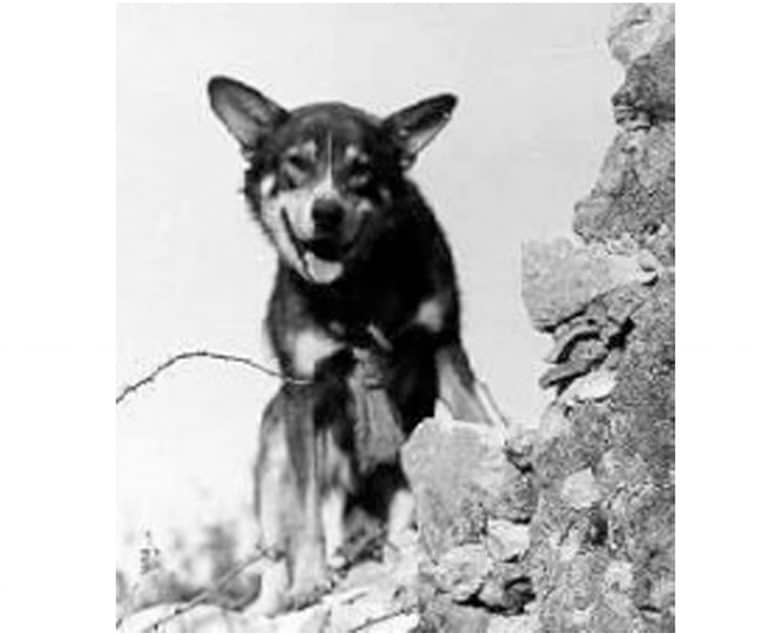

One way these prehistoric pooches started to demonstrate social attentiveness may have been by initiating eye contact with the villagers. A 2017 study of Dingoes supports the theory that early canines learned to look at people to establish a connection. These Australian feral dogs will gaze at humans for short periods of time while wolves avoid direct eye contact.

Researchers believe that Dingoes originated from partially tamed pups which reverted back to the wild after humans brought them to the isolated continent. Because these pooches had some contact with early men, they had behaviors that may show a stepping stone on the way to domestication. (17)

Phase Three: Domestication

As prehistoric dogs became less fearful and more attentive around humans, they developed cooperative partnerships with the villagers. Wolves had a history of cooperating with other members of their species. They would band together in packs to hunt and raise their young. When these animals became more closely associated with human settlements, they soon learned to work alongside these different creatures.

In the early stages of domestication, pooches served practical purposes. They helped around camp with the hunting, herding, and guarding. Over time, the mutually beneficial relationship evolved into something more. Humans and dogs developed a special bond and our four-footed pals became more than beasts of burden.

But just how did dogs become pets? The answer may lie behind a facial feature known as, “puppy-dog eyes.”

Remember the Dingoes? They will meet the gaze of a human in short glances. But our furbabies can stare longingly at us for extended time periods. When domestic dogs developed this ability, they were able to cause a chemical response that creates an emotional bond.

Scientists in Japan studied the effects of a dog’s prolonged gaze. They discovered that the interaction causes a mutual release of oxytocin. This hormone is instrumental in the mother-child bond. During the prolonged gaze, both dogs and people experience emotional bonding from the chemical release.

But that’s not the only thing that stimulates bonding. Anatomical changes in the canine skull and facial muscles appear to heighten this chemical response.

The Role of Skull Anatomy

As dogs evolved from wolves, their skulls retained some infantile characteristics into adulthood. Today’s canines have a puppyish face that humans find aesthetically appealing. Their appearance elicits a “baby schema response” or “cute response.” In this response, the stimulus of the pup’s facial structure causes positive feelings and a desire to care for the animal. (18)

It’s possible that humans selectively bred dogs for this desirable trait. The other possibility is that those animals with a more puppy-like appearance fared better in the villages. Either way, the change in anatomy lends itself to people showing affection for dogs.

The Role of Facial Muscles

Earlier we mentioned that dogs, with the exception of Siberian Huskies, have a developed levator anguli oculi medialis muscle. With this muscle, pups can lift their inner eyebrows. When a pooch uses the muscle, the eyes appear larger and more infant-like. In addition, the expression mirrors the human countenance when someone is sad. Both of these factors can encourage nurturing response in people. (19, 20)

The puppy-dog eyes help to endear our pups to us and build the dog-human bond. Animals that could communicate this way with their masters were able to thrive and pass on the genetic trait.

It took thousands of years, but over time dogs transitioned from living on the edges of human communities to living as our close companions. Today, pups work alongside people in a variety of ways.

Most of today’s pooches might be pets, but we still put some canines to work serving our country. Military pooches have been working for centuries in various countries. Let’s take a look at war dogs in America.

The United States relied on dogs to assist unofficially in the war effort in World War I. But when the second World War came, the country established a War Dog Program called the K-9 Corps. At first, the military sought publicly owned dogs. They had to be from particular breeds like Dobermans, Airedale Terriers, Boxers, and Labrador Retrievers. The animals also needed to be 1-5 years old, in excellent physical shape, and demonstrate “watchdog traits.’ Later, the government raised and trained their own animals.

The US Military has used dogs in both world wars, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, in Middle East conflicts, and they continue to work today. Some notable hero pups include:

Sergeant Stubby

a Staffordshire Terrier – Stubby worked during World War I. He once saved the 102nd infantry division when he alerted them to an early-morning mustard gas attack. This war dog also attacked a German spy and survived life-threatening injuries.

Chips, a German Shepherd/Alaskan Husky/Collie mix

Chips earned a Purple Heart and Silver Star for his service during World War II. He was instrumental in the capture of 14 Italian soldiers when his company was invading Sicily.

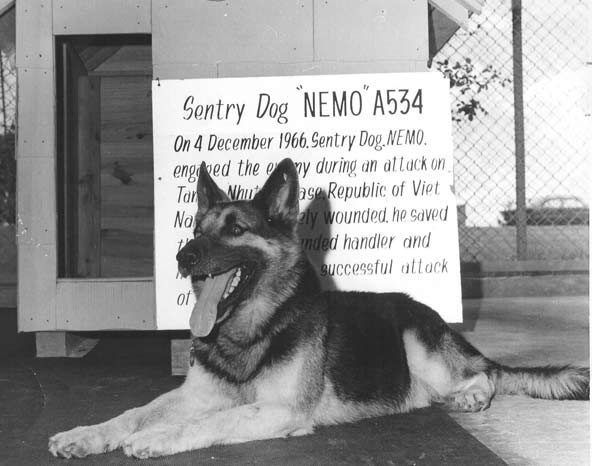

Nemo, a German Shepherd

During the Vietnam War, Nemo served as a patrol dog on an airbase. He and his handler were on patrol when they were attacked by Viet Cong Guerillas. His master took out two of the attackers, and Nemo held the rest at bay until reinforcements could arrive. The brave pooch lost an eye in the crossfire.

Cairo, a Belgian Malinois

As a member of Seal Team 6, Cairo participated in the mission that resulted in Osama Bin Laden’s death.

Over the years, canine war dogs have served a variety of roles:

- Patrol and guard dogs

- Couriers and scouts

- Morale boosters

- Rat catchers

- Helping to lay communication lines

- Carrying mines under enemy tanks

- Paratroopers/airborne dogs

- Explosive detection

- Serving on special operations assault teams

An Enduring Relationship

Humans and dogs have come a long way since grey wolves first encountered people. Of all the domestication stories, the one between pups and mankind stands out like no other. In the words of Roger A. Caras,

“Dogs have given us their absolute all. We are the center of their universe. We are the focus of their love and faith and trust. They serve us in return for scraps. It is without a doubt the best deal man has ever made.”